The story of Chennai is a story of paradox! On one hand, floods and heavy rainfalls inundate the city almost every few years; on the other an acute water shortage plagues its people.

Chennai experiences heavy rains roughly once every 10 years – 1969, 1976, 1985, 1996, 1998, 2005, 2015.

The 2015 floods in Chennai claimed more than 400 lives and caused enormous economic damages.

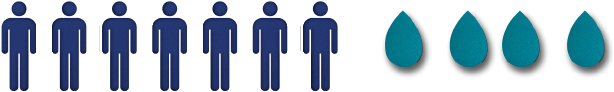

Against a demand of 1200 million litres per day (MLD), the city’s supply is a mere 985 MLD.

Downstream the Retteri lake, there were once no less than 16 water storage tanks. Today, none of these remain .

Chennai’s water story wasn’t always like this. It was replete with examples of traditional water storage structures like eris (tanks), ponds, temple tanks, wells and a number of other wetlands. However, another narrative soon took over. Chennai, unable to preserve its rich examples of water storage and rain-water harvesting systems, quickly became a victim of extreme water scarcity and floods.

The loss in wetland area has led to a drop in the city’s water table - pushing Chennai into a severe water crisis.

Moreover, in the absence of any perennial rivers in or around the city – Chennai remains highly dependent on groundwater for its water needs, making matters worse for the city.

The Chennai floods of 2015 were not a natural disaster!

As the city’s drainage system became non-functional and its wetlands were blocked with the excessive garbage thrown into them – the 2015 floods were caused by the city’s own inefficacies.

Wetlands such as marshes and floodplains act as natural sinks and flood water absorbents. They play a crucial role in reducing the impact of flooding. In the absence of these, flood water flows with greater force and in larger amounts, leading to bigger losses.

Velachery, a residential area in Chennai, is a good example of what can happen to a city if its wetlands are not preserved. The area was the worst affected during the 2015 floods and gets flooded every November – simply because the Pallikaranai, a marshland next to the area, has been encroached upon and reduced to less than one-tenth of its size.

allikaranai, now, can no longer absorb excess amounts of rainwater to protect Velachery from being flooded. This is however, only one instance.

Since 1999, the city’s concrete structures have increased nearly 13 times. Its floodplains and open areas, however, have been reduced by a fourth.

As encroachment and unchecked construction activities are taking over wetland areas, almost all of the city’s wetlands are vanishing one by one.

Every day, 1,500 tonnes of waste is dumped into the Pallikaranai - the only surviving wetland ecosystem of the city and one of the last remaining natural wetlands of South India.

Due to unplanned solid waste dumping, Chennai’s groundwater has been severely polluted – affecting the health of the residents of the city. Dumping waste into wetlands clogs them up, resulting in increased floods, water contamination and lower water levels.

Moreover, increased urbanisation and severe loss of green spaces and wetlands have rendered the city incapable of dealing with heavy rainfall, leading to excessive flooding!

Chennai has witnessed a tremendous growth in its manufacturing, retail, health care and IT sector in the last 10 years. With an urban population density of 14,350 per square kilometre, Chennai has overtaken Delhi as the third densest city in the country.

From 5.8 million in 2001, the population of Chennai Metropolitan Area has increased to 8.9 million in 2011!

The city’s population is growing at a steady rate. Its wetlands, however, are not.

This means that in a few years, there will be even more pressure exerted on the city’s finite and (already) over-exploited resources – pushing it into a much severe water crisis.

Chennai and its people need to take conscious measures in order to ensure that the city does not run out of water.

If dumping of waste is banned and water channels rejuvenated, around 60% of Chennai’s wetlands can be saved.

A number of governmental and non-governmental organisations are working on wetland restoration and towards safeguarding the biodiversity that thrives on these water bodies.

A consortium of NGOs in the city is working together with a united objective - to save the unique Pallikaranai marsh ecosystem. Efforts are constantly being made to conserve wetlands through research, advocacy and by raising awareness.

However, it is not only the government or NGOs that can play a crucial role in deciding the fate of Chennai’s wetlands.

Click here to see what you can do to help our taps, our wetlands and our cities from running dry!

Pallikaranai is a freshwater marsh in the city of Chennai and is home to several rare/ endangered and threatened species. The marsh is also a forage and breeding ground for thousands of migratory birds from various places within and outside the country.

About 40 years ago, Pallikaranai used to cover an area of 50 sq km but it has now been reduced to a tenth of its size. 90% of the marshland has been lost to construction of IT corridors, gated communities, garbage dumps and sewage treatment plants.

The lake that once spanned over 100 hectares has now been reduced to one-tenth of its original size. As its water levels are declining and the quality of its water being affected, activists are urging the Public Works Department (PWD) to save the remaining portion of the precious water body.

In 2014, more than 150 members of various associations and children participated in a lake cleaning campaign initiated by the Adambakkam Lake Cleaning and Rejuvenation Committee.

Mangal Lake lies in the northern part of Mogappair. Spread over and area of seven acres, the lake is a landmark for the area and serves as a groundwater recharge source for several neighbouring localities.

However, it is heavily contaminated by effluents from adjoining industrial estates.

These are twin lakes located in Manali and Madhavaram in Chennai. According to a recent study by Nature Trust, an NGO monitoring urban wetlands, about 55-60 species of birds are sustained by these wetlands.

However, once spread over 150-acres, the two lakes have now shrunk to half their size - reasons being indiscriminate dumping of garbage, sewage and illegal construction.

In order to protect the lakes, residents from the area have launched a campaign – bringing hope for the wetlands.

Ambattur is a rain-fed reservoir that spreads over an area of 100 acres.

For many decades now, the reservoir has served as a source of drinking water for thousands of Chennai residents and recharged ground water tables in the city.

However, at present, the lake has encroachments along its bunds. The outlets that connect the lake to the neighbourhood are also being misused to discharge sewage water into the lake.

Residents, in hope of conserving the wetland, want to convert it into a tourist destination with modern facilities such as seating arrangements, water towers for bird watching and boating services. They feel that this will protect the water body from sewage inflow and encroachments.

Pulicat is a lake of two cities – with 96% of it flowing within Andhra Pradesh and 3% in Tamil Nadu. After the Chilika Lake, it is the second largest brackish water lake or lagoon in India.

The jheel measures 450 sq km in high tide and 250 sq km in low tide; and also serves as a bird sanctuary. Its rich flora and fauna support not only numerous species of birds but many active commercial fisheries.

The jheel, however, is threatened by pollution from sewage, pesticides, agricultural chemicals, industrial effluents and oil spills from mechanised boats.